In a dramatic reversal, the agency that regulates the state’s massive ride-hailing industry has proposed that annual safety reports filed by Uber and Lyft should be presumed public.

A San Francisco Public Press investigation published Jan. 7 found that the California Public Utilities Commission, the primary regulator of the state’s ride-hailing industry, has permitted the firms to file the reports confidentially on the basis of a single sentence inserted into the regulations as footnote 42, without prior public notice amid heavy industry lobbying.

Citing the footnote, the commission has steadfastly concealed reports on thousands of ride-hailing accidents during the last six years and has refused to release the data to the public, the media or even other government agencies.

The commission’s extreme secrecy on the annual reports has long frustrated local government officials, who have said they needed the information to make policy on traffic, infrastructure and vehicle emissions. Several officials have complained that the agency — the only one to collect comprehensive data on the state’s ride-hailing industry — seemed indifferent to community needs.

In the proposed decision, issued Feb. 7, the commission said it would “delete footnote 42.” Going forward, each annual report would be presumed public unless the ride-hailing company could justify, with sworn legal arguments and specific facts, why it should be secret in whole or in part.

The proposal set out the agency’s reasons for the reversal. It noted that when California became the first state to regulate ride-hailing, in 2013, it required each firm to submit annual reports on traffic accidents, driving under the influence and other problems with drivers, as well as the number of trips by ZIP code and time, and accessibility to disabled riders.

The commission said it allowed the firms to submit the reports confidentially because it accepted their claims that making the data public could compromise sensitive information and place them at “an unfair competitive disadvantage.”

But since then, the agency said, it has gained a greater understanding of ride-hailing operations that requires ending the presumption of confidentiality.

At this point there are no rivals to Uber and Lyft’s huge market share, the commission said, a fact that undercuts their claims that releasing the data would harm their business. Since 2014, it noted, they have together provided more than one billion rides in California, compared with the approximately one million rides provided by the state’s 15 other, much smaller ride-hailing firms. Uber and Lyft combined occupy more than 99.9% of the market.

Meanwhile, the commission has gradually adopted stricter standards for regulated companies seeking to keep records they submit secret. For decades it was routine for firms in various industries to simply stamp their papers with a confidentiality notice, the agency said.

But the law has evolved and firms are “no longer entitled to a presumption of confidentiality,” the agency said. Under recent commission rules, they must make a detailed showing of why each page, section or field of a document must be confidential based on current law and the information at issue.

The commission said its proposed deletion of the secrecy footnote “aligns with California’s policy that public agencies conduct their business with the utmost transparency.”

The agency also said it had become aware of “the heighted public interest” in the annual reports.

Since at least 2017, the San Francisco City Attorney’s Office and other local agencies across the state have filed statements with the commission saying they needed the data to address concerns about public safety, traffic congestion and transportation management.

Uber and Lyft have staunchly resisted making the raw data public, telling the agency that it contained trade secrets and personal information. Uber also said it was concerned that local agencies would be unable to protect the information from hackers. Neither firm immediately responded to a request for comment.

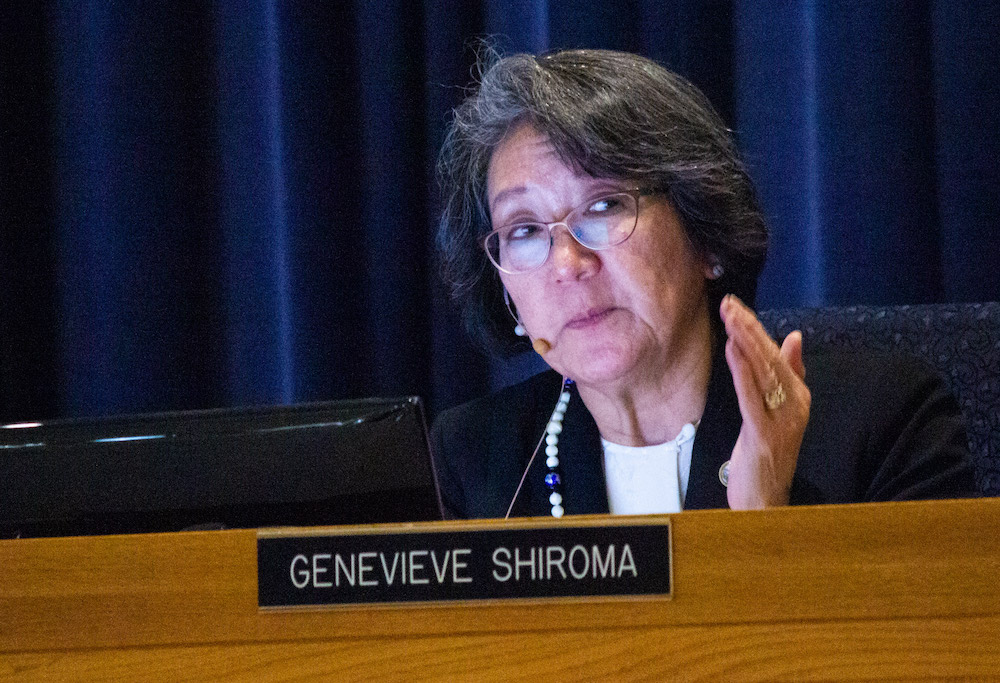

The proposed decision, authored by Commissioner Genevieve Shiroma, left unresolved the question of whether the commission would also make public the annual reports filed for the years 2014 to 2019. That matter would be addressed separately, it said.

Terrie Prosper, a spokeswoman for the commission, said the agency could vote on the deletion of the footnote as early as March 12. Interested parties may submit comments in advance.

Following numerous public records requests and inquiries about both the annual reports and the origins of footnote 42 by the Public Press, the commission announced on Oct. 25, 2019, that for the first time it would reconsider the footnote.

In addition to the shadowy origins of that clause, the Public Press found that a previously unreported PowerPoint summary of the secret annual reports showed that the number of accidents acknowledged by the ride-hailing firms totaled more than 1,100 per month statewide as of August 2015, with incidents such as drivers crashing into other vehicles and running over customers’ feet.

Moreover, a separate study by the commission and the California Department of Insurance, also previously unpublicized, determined that insurance companies incurred $185.6 million in payouts from 9,388 claims related to traffic accidents involving ride-hailing vehicles across California for the years 2014 through 2016.

Meanwhile, the San Francisco Police Department’s spot enforcement operations found three years in a row that more than half of the traffic citations issued in busy downtown areas went to ride-hailing drivers for violations such as blocking bike lanes. Of the 47 traffic fatalities in San Francisco from 2018 through August 2019, seven involved ride-hailing vehicles, according to police records.

In response to the Public Press’s investigation, two state legislators and the chairman of San Francisco’s transportation board said the commission should release the secret safety records.

Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez, a San Diego Democrat, criticized the agency on Twitter for giving a “pass” to the industry on transparency and safety, adding in an interview that “we’re prepared to legislatively override, if possible, to audit and use all the tools possible to get them to change their procedures. It’s too important.”