When we report a story, it can involve numerous interviews, sources speaking on background or deep dives into government or corporate records. But sometimes it’s amazing what a small object can reveal.

Like the rubber stamp recently discovered by Liana Wilcox, producer of the San Francisco Public Press’ podcast “Civic,” when she was helping her mother clear a storage area.

“I was with my mom going through some of her keepsakes and found a stamp that read ‘Lesbian Money.’ My mom told me that she found it in our old church’s basement,” Wilcox said, adding that she feared the rubber stamp had a sinister connotation.

“I immediately thought it was some sort of exclusionary practice, but that didn’t feel right considering the church we went to, the First Congregational Church of San Francisco, called themselves ‘open and affirming,’” she said.

Wilcox mentioned the stamp during one of our staff meetings, and I said “Oh, no that was a way we tried to raise awareness about the LGBT community back in the old days.”

As a young gay activist and budding journalist in Salt Lake City in the early 1980s, I vaguely remembered stamps like that one. I reached out to a dear friend to see if she remembered lesbian money.

Becky Moss is a longtime LGBTQ+ community organizer in Salt Lake City. She and I co-hosted the radio show “Concerning Gays and Lesbians” in Utah in the early ’80s. Moss said activists around the U.S. were stamping bills to show the financial power and size of the greater queer community back in the late 1970s.

“Separatist lesbian communes would stamp all of their bills before coming into town for supplies,” she said. “But I remember it being more widespread than that, it was really a nationwide thing.”

A number of sources trace the first “Gay$$” and “Lesbian Money” stamps — sometimes marked with a pink triangle — as having originated in San Francisco in the mid 1970s. The pink triangle was used by the Nazis in Germany to identify gay men in concentration camps and was co-opted as the symbol of the early gay movement before the rainbow flag mostly supplanted it.

Wherever the money stamping started, by 1986 it had drawn the ire of the Reagan Administration. The U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Illinois issued a cease-and-desist order to lesbian and gay bar owners in Chicago who were stamping all the bills coming through their businesses to the tune of $5 million a year. Government officials said the campaign violated federal law against defacing currency. But the legal action foundered at least in part because it was nearly impossible to determine who was responsible — anyone could stamp bills, anywhere. The Treasury Department also determined that most of the bills were still “fit for circulation.”

Money stamping campaigns grew quickly to the point that finding some kind of queer stamp on currency was fairly common in the 1980s. It made an impact in an era when LGBTQ+ representation in film, television and the press were rare.

Campaign Against Discrimination

Money stamping campaigns were also used to counter discrimination against people with HIV and AIDS in the 1980s. One campaign out of Utah unfolded when Moss visited a restaurant in a suburb of Salt Lake City in the late 1980s.

“My sister, who had AIDS, and I were at a restaurant in Bountiful, Utah,” she said. “After the meal, the staff threw our plates in the garbage.”

The Salt Lake City branch of ACT-UP, the AIDS activist organization, decided to use an “AIDS Money” stamp to fight such blatant discrimination against those perceived to be infected with HIV.

“They all went to the restaurant and bought things like pie or french fries and then paid for them with the stamped money,” Moss said. “The activists made the point that the owner would now have to throw away all the plates used to serve them or stop the practice.”

“AIDS Money” stamps remained part of the nationwide effort to raise awareness through the 1980s and ’90s.

Becky’s sister Peggy Moss Tingey died of complications from AIDS in March 1995, just nine months after her young son Chase died from the virus. Both passed away just before the HIV protease drug cocktail was starting to become available.

Other Stamping Activism

Recent money stamping campaigns included “I grew hemp” stamps, promoting marijuana legalization, placed on $1 bills near George Washington’s portrait. The idea was taken up by groups advocating for the Second Amendment — “gun owners money” — and even campaign finance reform, with the Ben and Jerry’s Foundation organizing “stamp money out of politics” stamps in 2012.

A campaign in 2016 used large stamps to place Harriet Tubman’s face over the $20 bill portrait of Andrew Jackson, after the Trump Administration overruled the Treasury Department’s plan to replace Jackson with Tubman by 2020.

While the LGBTQ+ movement used stamping to great effect, it was by no means the first to spread the word by customizing currency.

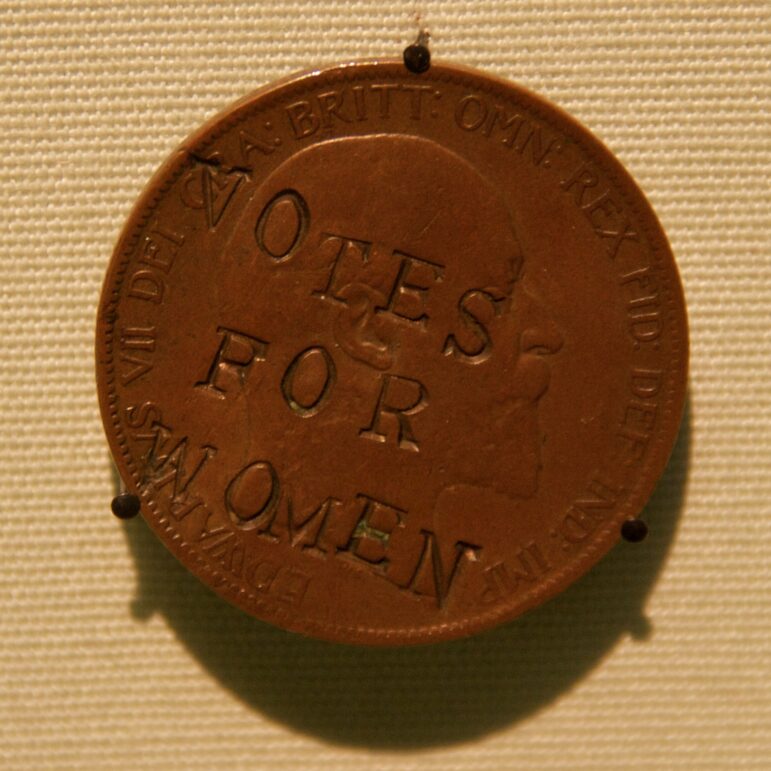

Before World War I, British suffragettes stamped pennies with the words, “Votes for Women.” Only a handful of the coins still exist. But just as the U.S. Treasury Department declined to withdraw bills with “Lesbian Money,” the British banking system declined to take the low-value marked pennies out of circulation.

Without suffragettes breaking the first chain of patriarchal thinking by winning the right to vote, there would have been no LGBTQ+ rights movement. Discrimination against women — sexism — is the basis of hatred of different sexual orientations and gender identities.

Both the British women who had to strike each penny 13 times — engraving their words letter by letter — and those who inked rubber stamps over and over again used their spending power to wear down conspiracies of silence, one tiny message at a time.