Berkeley is accelerating plans to more humanely deal with homelessness in the wake of a San Francisco Public Press report on a chaotic encampment raid in October, and city staffers say they will start collaborating with unhoused people and homeless advocates when planning to clean or clear large encampments.

Several city departments are changing procedures in response to complaints from those living in encampments and their advocates, and from residential and commercial neighbors.

Here are some key changes:

- Berkeley will increase trash pickups to several times a week and do more frequent street cleaning to improve overall sanitation and living conditions.

- The city auditor is reviewing the effectiveness of the city’s homelessness services.

- The police department is reducing its involvement at encampment abatement operations.

- The fire department is providing unhoused people with basic fire safety guidelines.

- The city manager’s Homeless Response Team has taken steps to improve communication with residents at the largest encampments in West Berkeley through community meetings and new “Good Neighbor Guidelines” that explain what conditions would trigger a city intervention.

- The city has also applied to the state for an Encampment Resolution Funding Grant Award to lease a motel that it would use to provide temporary shelter.

In my capacity as a professional journalist, I reported for the Public Press on the aggressive October encampment cleaning that upended the lives of more than 50 people living near Eighth and Harrison streets and brought the city’s response to homelessness under scrutiny.

I was able to document and photograph the 12-hour encounter because it affected me, too. I am part of a community of people living in tents and vehicles who have been displaced from other encampments around the city, including the Berkeley Marina, the Gilman Underpass, Seabreeze, Ashby Shellmound, People’s Park, the Grayson Street Shelter, Here/There Camp, Shattuck Avenue and the Second Street camps.

In the wake of photographic evidence from the October encampment cleaning, which exposed the city’s poor communication, lack of transparency, and failure to provide adequate shelter and support to unhoused people, city departments are under review.

Berkeley Senior Auditor Caitlin Palmer wrote in an email that, “We plan to work on the audit in the fall and hope to issue it sometime next year.”

The Berkeley city manager in July concluded an investigation of Berkeley police officers involved in the October encampment sweep who sent text messages that the Berkeley Police Accountability Board said showed “anti-homeless and racist remarks.” The city manager’s office, which hired an independent company to conduct the investigation, issued a report that the investigation found no wrongdoing. But the office has indicated that it will not release further details from the investigation, which it deems confidential.

Aiming for Clearer Communication

Peter Radu, assistant to the city manager, said the city acknowledged that it had mishandled encampment cleanings and used “overhanded” measures that included the destruction of personal property and giving vague, sometimes conflicting instructions to encampment residents. He acknowledged his own role in those events and said that he and the city wanted to work with unhoused people and homeless advocates to rectify the situation.

“I am genuinely sorry,” Radu said to community members gathered at Eighth and Harrison streets. “We’re trying to start something new, and work more with you as opposed to against you moving forward.”

On July 10, dozens of people gathered under and around a gray shade structure at Eighth and Harrison streets. Radu addressed the crowd of outreach workers and encampment residents to tell them that the City Council would soon approve a new shelter, referring to the planned motel conversion. He did not say whether the city would close the encampment, noting that Berkeley has more unhoused people than available shelter spaces, but said that residents in the area would be prioritized. The city has not announced a date for when it plans to begin operating the motel as a shelter.

“Call it a ‘closure’ or call it something else,” Radu wrote in an email asking for clarification about future plans for the encampment. “We do have (1) an opportunity to move people inside with a new resource, and (2) we do have infrastructure repair and construction needs in the area. People cannot live in construction zones.”

Radu’s efforts to establish trust have been met with mixed reactions from people living in the camp and their advocates. While some said they appreciated this newfound willingness to cooperate, others remained skeptical.

“You had consequences from your actions and now you are here,” said Chloe Madison, a camp resident on Eighth Street. “I’ve seen this side of you before, and I’ve also seen the guy who steals people’s homes.”

Many unhoused people say they continue to feel harassed no matter how much they do to avoid residential neighborhoods, because Berkeley staffers have shuffled them around the city with repeated encampment cleanups and closures.

“Just in the past few months, like Seabreeze. I’ve had like 10 camps in the last couple of years,” said Ron, a resident from the Second Street encampment. “You have herded us here.”

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Okeya Vance, Homeless Response Team supervisor, prepares a public notice for property retrieval that she will leave for Indo, who was away from his makeshift home when city workers arrived. Peter Radu, assistant to the Berkeley city manager, digs through a pile of clothes and puts them in plastic bags that the city will store for Indo to retrieve.To address such grievances, Radu began working with two of the largest encampments in Berkeley, located near the intersections of Second and Page streets and Eighth and Harrison streets. He said the city and residents needed to find middle ground and take a collaborative approach to addressing the sanitation issues on the streets.

“There’s a competing need for space,” Radu said at an Eighth and Harrison streets community meeting. “So, we’re just trying to find a solution that keeps everybody safe and that allows the community to kind of have a shared use of this public space.”

In April, Radu held the first of three community meetings and presented a report to people living at the Second Street encampment, and said that if residents addressed safety concerns voluntarily, the city would not enter anyone’s vehicles or tents. He said that because of fire risk, residents would not be allowed to live in other kinds of makeshift structures.

Residents who attended the meeting said they were willing to work with the city, but many also shared their experiences of repeated property loss due to previous sweeps. Ron, who gave only his first name, recounted how he lost his belongings when he arrived late during the last cleaning at Second and Page streets. He said he jumped on the back of the garbage truck to salvage his personal belongings. He was able to save a few items.

“I was five minutes late, five minutes late, and I lost everything,” Ron said at the community meeting. “I had things that I carried from town to town. I had things in there for years.”

Alice Barbee, who lives in the unhoused community at Eighth and Harrison streets, said the city previously gave instructions, which residents followed, and then discarded their possessions anyway.

“You say to get it all across the street if you want to keep it safe,” Barbee said. “But you come and you take that stuff, too. All of it and then call it trash?”

In May, residents of both communities asked for reassurance that no one would enter their households and throw away their possessions.

“We have not been as transparent and communicative as you guys would have liked and as we could have been,” Radu said to a gathering of Second Street residents. “I just want to acknowledge there were clearly misunderstandings and miscommunications on our account.”

In May, Radu tried collaborative cleaning at both encampments, asking residents to voluntarily address safety concerns highlighted in his reports. He deemed those events a success.

“We schedule a deep cleaning together and, voluntarily, give us what you don’t want,” Radu said to Eighth and Harrison residents, noting that the city staff had hauled away 11 tons of debris the previous week from the community living near Second and Page streets. “It was all voluntary. None of it was forcefully taken from anybody. We didn’t enter any tents.”

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Peter Radu, assistant to the Berkeley city manager, speaks with a Second Street resident about demolishing the makeshift structure where she was living because it was deemed a fire hazard. Berkeley Fire Marshal Dori Teau says wood structures have higher heat output and longer burn time, raising the risk that they could cause fire to spread. In contrast, tents burn faster, reducing the risk of prolonged fires.But the city does not have a policy for preserving the belongings of someone who is not on site when it conducts a cleaning operation. This means that residents living in tents or makeshift shelters risk losing their possessions when they leave their homes.

The city has also made agreements with surrounding businesses to keep people from camping on their sidewalks. Public notices are issued to residents camping outside of designated zones along Seventh and Eighth streets citing the city’s sidewalk ordinance and prohibition of bulky items in commercial corridors. The notices direct people to a shelter that closed in December and is no longer in operation.

Sharing Public Space

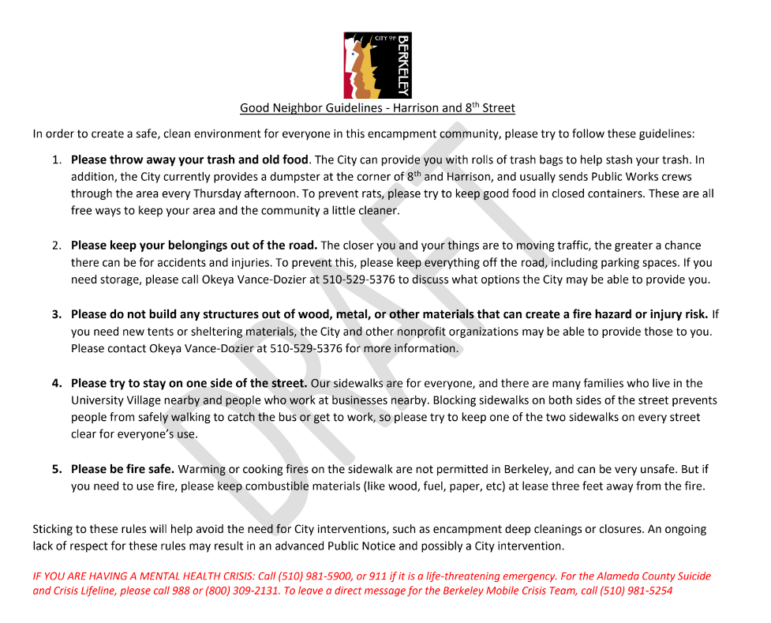

In an effort to get everyone on the same page, Radu asked a few homeless advocates to give him feedback on a draft of unofficial guidelines to maintain general cleanliness in the neighborhood and improve interactions with the surrounding business community.

Radu said he hopes the “Good Neighbor Guidelines” will help establish a better working relationship between encampment residents and the city staff. He is seeking additional community input on the draft.

Berkeley City Manager’s Office

Draft No. 4 of Berkeley’s “Good Neighbor Guidelines” as of July 18, 2023.But the new procedures are challenging for a few residents who sleep on the open sidewalk and struggle with mental health issues. They are in survival mode and have trouble following rules about storing their belongings and discarding food scraps to avoid attracting vermin. And so, they are constantly at risk of having their possessions thrown away during weekly street cleanings.

“The Guidelines are rules the City wants people to follow. The guidelines say ‘Please,’ but behind that ‘please’ is the threat that if they are not followed, eviction, arrest, or a citation will result,” wrote Osha Neumann, a Berkeley civil rights attorney, in an email seeking his comment on the guidelines. “The City needs to realize that a great number of the people out there have significant disabilities, mental and physical, which make following rules difficult.”

The Public Press asked for reactions to the guidelines from Berkeley Mayor Jesse Arreguín and all of the City Council members, about half of whom replied by email. Councilmembers Sophie Hahn, Ben Barlett, Rigel Robinson, and Mark Humbert declined to comment on the city’s response to homelessness despite multiple requests.

“These are temporary, common sense guidelines specifically for this neighborhood during the transition to the Super 8 motel,” Elgstrand wrote on behalf of the mayor. “These guidelines will help ensure the safety and security of encampment residents and neighbors.”

Councilwoman Susan Wengraf wrote that she agrees with what Berkeley city staff is doing and that “Berkeley is moving in the right direction.”

Councilwoman Kate Harrison wrote that “it is critically important that while the City makes these requests of unhoused and housed people in our community, it simultaneously provides the necessary facilities and services that allow people to follow them.”

Councilman Terry Taplin has already promulgated a version of these unofficial rules on his website as his district also grapples with homelessness. “The Good Neighbor policy both increases transparency around what triggers a city intervention and provides recommendations to better manage the public right of way better and improve traffic and fire safety,” he wrote, adding that the city could take further steps to improve encampment sanitation.

“Conditions can be improved by waste pump-out services,” he wrote, also noting that the city’s Homelessness Services Panel of Experts has also recommended expediting the search for a new parking lot for the safe parking program. But no money was earmarked for it on this budget cycle, according to Radu.

Harrison and Taplin agree that the city needs to implement other changes, such as providing more permanent supportive housing and transitional housing programs citywide, in addition to resolving sanitation issues.

The state grant would allow the city to lease the motel for two years, and the city hopes funds from Berkeley’s Measure P, which passed in 2019, would pay for three additional years.

“We are working with the County and our nonprofit service providers in finding solutions that enable us to provide access to shelter and services beyond the Super 8 motel,” Elgstrand wrote. “Even if this one location reaches full occupancy, we will continue to do everything we can to target resources to the residents of this encampment.”

Looking for Representatives to Show Up

Despite recent developments, some encampment residents said they felt frustrated and abandoned by Berkeley city officials. They wondered why City Council members and the mayor attended a recent Gilman District Business Summit to talk with business owners but had not attended any of the encampment community meetings.

“As long as you ostracize people, and their issues are not as important as others, then anger and resentment starts to come in,” Merced Dominguez said at an Eighth and Harrison community meeting, adding that she wanted to see the Gilman District’s Councilwoman Rashi Kesarwani attend a future meeting. “We just want to have a dialogue with her to work something out. This is what she was voted in to do.”

Kesarwani replied to a request for comment with a general statement but did not directly answer questions about recent policy changes and how Berkeley staff is responding to homelessness in her district despite multiple requests.

Madison, another encampment resident, expressed her frustrations over email, writing that she hadn’t heard about the business summit and questioned the timing of that meeting, which portrayed unhoused people disparagingly, blaming them for criminal behavior and causing others in the neighborhood to feel fearful.

“For you to attempt to approach us in good faith only days later is super skeevy,” she wrote to Radu. “Super cool how we’re all lumped into being scary crime doers when all I do all day is attempt to further my career in a way that works with my mental and physical health.” She added that “excluding us from that meeting allows those narratives to perpetuate.”

Radu responded to Madison that he had recommended including encampment members and community advocates at the meeting with business owners, but that the decision was not up to him.

“You’ll understand that I don’t get to make all those decisions, but since then I HAVE recommended to the business leaders that they reach out to you and try to have conversations,” he wrote, adding that “I agree completely with you that the format of the business meeting was not conducive to such trust.”

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

A Berkeley Public Works employee retrieves a bike frame from the backhoe scooper and returns it to L.A., a Second Street resident, who reaches out to accept the frame. Since L.A. was not present when the area was being cleaned, some items outside his tent were discarded. L.A. inspected the scooper and saved a few more items.Some encampment residents are accepting, cautiously, what appear to be goodwill gestures.

“For a long time, I think it was a big battle. You guys don’t want to talk to us or work with us,” said Sarah Teague, a Second Street encampment resident, at one of the recent meetings.

“But you guys are making the initiative to come down here and talk to us personally. That’s a huge breakthrough,” she said. “I think it’s a big giant leap of faith for everybody.”

Full disclosure: Radu asked for Yesica Prado’s feedback on the Good Neighbor Guidelines and accepted a few suggestions to clarify wording but did not incorporate her other recommendations.